It can be really difficult to track the success of workforce development programs. Getting the information involves contacting program participants who may not receive or respond to emails or calls, and then asking them about sensitive topics such as whether they’re still employed and if they make enough money to support their family. And then there’s the data itself — many organizations just don’t have access to the right data or the capacity to analyze it.

In a first for the non-profit sector, last year Tipping Point began partnering with the California Employment Development Department (EDD), the agency that tracks wage data for all Californians, to better understand what’s working and what’s not for workforce development organizations. Tipping Point is working with EDD to collect and analyze wage data for our employment-focused grantees, starting with Opportunity Junction. The result? Groups will better understand their clients’ outcomes, giving more insight into how they can refine their programs to increase wages.

We sat down with Tipping Point’s Senior Director of Impact and Learning, Jamie Austin, to find out how this unprecedented partnership developed, and delve into how this data might improve the future of employment programs.

What data will this new EDD partnership provide and why is it so crucial for organizations?

JA: Imagine a sales team that successfully sells a product to a group of customers, but never finds out how they’re using the product or how the company could improve it. In the for-profit sector, there are entire market research departments built around learning from consumer data. But in the non-profit sector, organizations often have to fly blindly.

For example, organizations providing employment services and support have little information about whether a client got a job after leaving the program, if she held that job or if she earned a living wage. But that’s exactly the information organizations need in order to know if programs are working. And now we have access to that information.

This measurement seems so straightforward and yet, funders and practitioners have struggled to track how employment programs affect client earnings over a long period of time. Why is that?

JA: Organizations do their best to track how their clients fare over time, but it’s very hard to do. As a result, organizations have been doing their best with data that doesn’t give them the full picture. You’re reaching out to people with emails and phone calls, but you get low response rates — and even when you do get responses, you’re having to ask sensitive questions: what is your salary, did you lose that job, are you able to support your family, etc.? As you can imagine, these are difficult questions for anyone to answer, let alone someone struggling to make ends meet.

What changed? Why have we finally been granted access to this data?

JA: Last year, we were introduced to the team at EDD and asked if we could work together to address the data gap. We had assumed that they would be resistant, but soon we were talking with them about how to unlock the data. For a numbers guy, having access to this kind of information is like gold!

Tipping Point jumped at the chance to move this forward. Since we met with EDD, we’ve moved quickly to implement usable solutions, including translating the complex data into easily digestible data visualizations.

What was the first project you worked on with this data?

JA: The first step was to trial this new data access with a grantee. I immediately thought of Opportunity Junction because of its robust programs, strong potential for impact, and excellent data monitoring efforts. I had worked with their Executive Director, Alissa Friedman, over the years and knew she’d be game for this pilot project, even if it meant extra work.

Once Opportunity Junction was on board, we provided EDD with some basic information about a cohort of clients. Then, EDD sent back wage data — from both before program participants were enrolled to years after they had completed the program. We could track their progress over time with real, accurate data.

What did you find out from that first pilot?

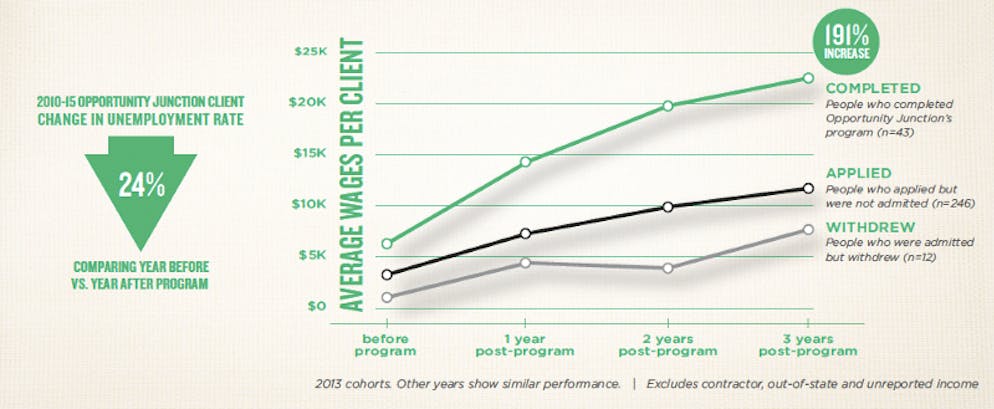

JA: Well, the first thing is that Opportunity Junction was ecstatic! They were able to truly see their program’s impact over time. The data showed that people who had completed Opportunity Junction’s signature employment program saw an increase in wages that was greater than those who applied but were not admitted, or those that were admitted but withdrew. Three years after they had completed the program, clients who completed Opportunity Junction’s program maintained higher levels of employment and wages in comparison to others — for one cohort, there was a 191% increase in wages!

And yet, total wages are only around $23,000/year, three years later. Can you talk about that?

JA: That’s right. Three years after graduating, the average annual wage of the 2013 cohort was $23,300. For a family of three, this is about 13% above the poverty line, and compared to the average earnings of similar individuals who did not complete Opportunity Junction’s programs, the salary of program graduates is considerably higher. Yet we all know about the high cost of living in the Bay Area — raising a family on around $23,000/year is an enormous challenge. This means we have much more work to do to ensure living wages and that clients are able to continue building skills that grow their income. It also raises questions about the data: we can’t get access to the number of hours that clients work, so we don’t know if clients are working part-time (perhaps by choice) or full-time.

Will this primarily be useful for workforce development organizations?

JA: We’re trying this out first with our employment grantees, but it’s really useful across a variety of organizations that want to understand how their clients do financially both before and after their programs.

Why has this information been inaccessible for so long?

JA: It takes a lot of work to gather information about people’s experiences, and often non-profits can afford to use only less-than-perfect data systems and have access to limited amount of information. Non-profit staff aren’t experts in tracking down clients: while they are very interested in how clients are doing, their expertise lies elsewhere. With the kind of data we’re preparing, they can now clearly see how clients are doing.

Knowledge of this impact is what drives people to work for non-profits — to know they are making a difference. People want to be able to do good and too often have little sense whether they actually are. Being able to see impact is a dream-come-true for any organization, and especially those that are data-driven.